Produced by:

“Today’s scientists have substituted mathematics for experiments, and they wander off through equation after equation, and eventually build a structure which has no relation to reality.” – Nikola Tesla.

Risk appetites are disconnected from reality; they are often theoretical. Unfortunately, many companies think strategically while remaining risk averse. While there are many methodologies and approaches to manage risk appetites, not many of them are highly executable, realistic and sustainable. Too many risk appetite frameworks fail because they are strategically and therefore theoretically driven. They often begin with the drafting of risk appetite statements which operations then must interpret to put into action.

Different mindset

“Our software requires a totally different mindset. Many people think in a linear way. We propose going back and forth between strategic thinking and execution disciple”, says Emmanuel Noblet – CEO of ngCompliance. His company has created software to challenge what he sees as a theoretical mindset that most organisations overly rely upon to manage risk.

The focus on the creation of risk appetite statements is often counterproductive and leads to much misinterpretation. An example would be a risk-averse pension fund, which is overly concentrating on a client-satisfaction objective. The Key Performance Indicator (KPI) in this case is the number of incidents the organisations are ready to accept in its client-related processes.

Noblet explains: “Let’s say this pension fund has 50,000 clients. The delivered service is a monthly pension payment. There are thus 50.000 x 12 = 600,000 “customer touchpoints” for this process. The initial risk appetite statement stated, “We do not tolerate more than 10 incidents per year.” To quantify this, he says 10 occurrences out of a 600,000-possibility universe means that the board’s confidence interval was set at a stunning 99.9983%.

By setting the risk appetite to 99.9% turns the statement into: “We accept up to 600 incidents a year.” This is quite a difference. Even 99.99% translates into 60 incidents a year, far beyond the initial statement. He elaborates: “The problem of devising a risk appetite statement means that you are not confronting reality; you are thinking strategically. The confidence level is also set too high. If you want to set a realistic, executable and sustainable risk appetite you have to confront your ambitions and reality. Tolerating 10 incidents a year is unrealistic – wishful thinking.”

Confront ambitions

He adds: “You need to confront your ambitions by stepping outside of the board room. You might have a brilliant vision, but it might be worth nothing. That’s the key message of the story. We don’t feel comfortable in theory only; we need to deliver something that works both for the generals (the board) and the privates (the employees) day-to-day. The story is of the general who goes out onto the field, rather than a boardroom general.”

To make matters worse he finds there is a failure to integrate KPIs with the reality of the world. His company, therefore, proposes a zig-zag line between strategy and operations, rather than the traditional linear way of strategic thinking. The key objective is client satisfaction, which is achieved by demystifying risk client’s risk appetites to ensure that they are executable, realistic and sustainable rather than just flights of fancy.

We don't feel comfortable in theory only; we need to deliver something that works both for the generals (the board) and the privates (the employees) day-to-day. The story is of the general who goes out onto the field, rather than a boardroom general.

Own Risk Assessment

ngCompliance works with its clients to demystify risk appetites and offers an example of a pension fund based in the Netherlands. In 2016 at the beginning of the adoption of IORP II, which requires organisations to perform an “Own Risk Assessment” where there is a significant change in the risk profile of a specific pension scheme, many ngCompliance’s clients asked about their risk profiles. The trouble is that, despite this phrase being cited multiple times in the text, no exact definition could be found.

“We did not want to propose yet another conceptual framework but instead, we wanted to compose a fully workable option in our risk management solution (answer the questions; fill in the figures; watch and manage your risk profile)”, he explains before revealing that the solution is now up and running. Banks, insurance companies and pension funds are among the firms who’ve implemented ngCompliance’s solution, but nothing hinders a non-financial company to make use of it.

No matter who wishes to implement and fulfil an executable, realistic and sustainable risk appetite, there are 5 steps to consider. The first step begins by asking: “What are your objectives?”. Yes, of course, each business is unique. But ngCompliance is a software company, not a consulting firm. So, there is a need for a no-nonsense framework that ensures the solution works.

Not all the following categories need to be part of a risk profile. However, any business can define all its objectives by using these 8 categories:

– Financial – Financial stability;

– Financial – Revenue and profit generation capability;

– Financial – Liquidity;

– Non-Financial – Client satisfaction;

– Non-Financial – Partners (employees, third parties such as suppliers and partners…);

– Non-Financial – Products and services (including markets and distribution channels);

– Non-Financial – Community (including press and social media) and compliance;

– Non-Financial – Governance and culture.

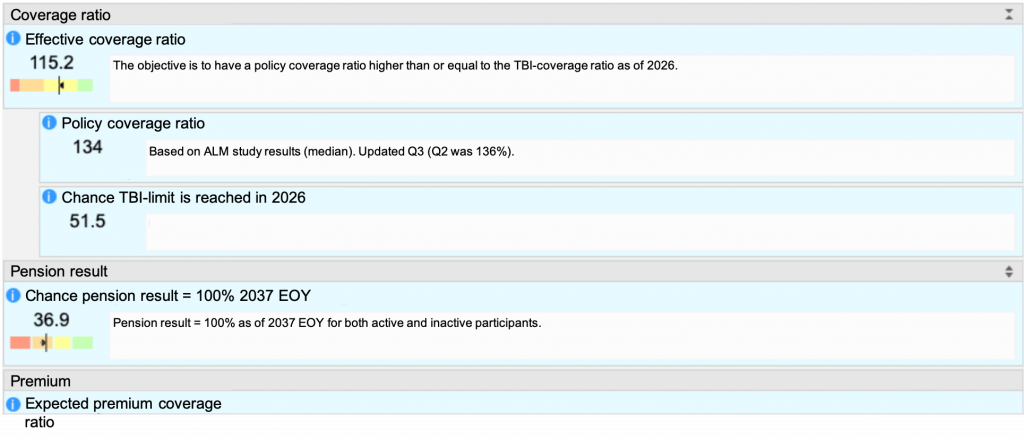

He reminds us that, “although declinations are infinite, such a blueprint facilitates the definition of objectives and their related KPI’s. For each formulated objective, a primary KPI and secondary KPI’s are defined. This may be for a pension fund’s financial stability, as measured using the coverage ratio.

Defining risk appetite

During the second step, he explains that the traditional theoretical approach is to first form “risk appetite statements”. Experience shows that this is counterproductive and can lead to misinterpretation mentioned earlier in this article. Let’s now directly jump to the risk appetite and risk tolerance levels’ definitions, which is made easy by the definition of KPIs. Here are his thoughts on how to go about this:

– The first step is to define the KPI’s level, which is deemed unacceptable: in other words, where does the red zone begin?

– The second step is to define the KPI’s values within which the objective is fully achieved: in other words, where is the green zone?

– The third step is to define risk tolerance. Risk tolerance defines or quantifies KPI’s values (or the maximum amount of risk) that the organisation is technically able to assume at the cost of triggering a “stop-loss” strategy. For example, this may be the level of risk the organisation can temporarily absorb or manage by breaching factors such as its capital base, liquidity levels, borrowing capacity or covenants, reputational and regulatory requirements, operational constraints and obligations to shareholders, customers and other stakeholders. In other words, these are the boundaries within which a corrective action plan is necessary. The lower bucket value is that of the red zone and very often, the higher bucket value is a contractual, mandatory or regulatory level (e.g.: for a pension fund, coverage ratio between 85-90% and 104,3% triggers a corrective action plan (“herstelplan” in Dutch). This is the orange zone.

– The fourth step is easy: between the green and the orange zones, one can find the “yellow” zone, i.e. the KPI’s values that the organisation is technically able to assume without triggering a “stop-loss” strategy. Note that this is the most interesting and delicate zone: one can accept a KPI to “fall” in that zone in hope for its reward to be higher. This is usually the toughest zone to define, which is why our approach defines it by default.

Noblet explains that the green and yellow zones together form the risk appetite; and the green, yellow and orange zones together form the risk tolerance. The red zone is the “no-go” zone.

Jump to execution

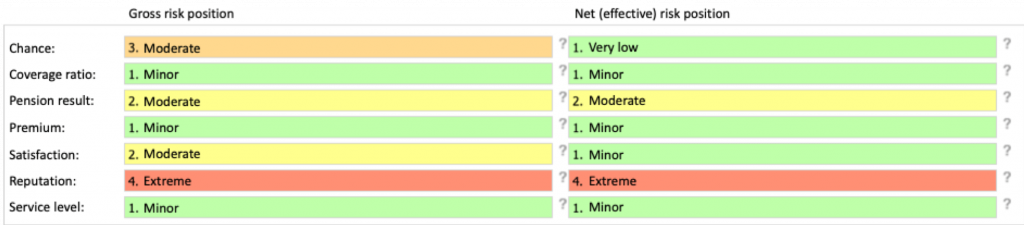

Once objectives and related KPI’s are defined, he says the trick is to accept to stop the strategic exercise and jump to execution. This involves splitting the individual risk’s impact assessment (gross, i.e. before controls and risk mitigations and net, i.e. after controls and risk mitigations) alongside each of the retained objectives.

Noblet argues that there is one clear disadvantage to this approach: each risk assessment will require as many impact score as there are objectives: “The advantages easily outweigh this disadvantage. Not only are the impact assessments more consistent across risks, but first-line managers finally have established a common language for impact assessment, drastically reducing the time spent to align the different points of view, and first-line managers can easily express what they really think about certain controls.”

“We witnessed a fantastic discussion between one of our clients’ risk manager and relationship manager about a new compliance control”, he comments before explaining: “The risk manager was reluctant to go through all risk assessments again to individually score by objective, whereas the relationship manager was just enthusiastic about this: indeed, she could easily signal that although a control will increase the score in terms of compliance, it will decrease the customer experience, triggering a fantastic discussion both at Board and field levels.”

Estimate marginal impact

Once all identified risks are assessed, he advises that it’s then possible to estimate the potential marginal impact of each of those risks on the retained KPIs. There are two ways to do so:

1. Either go for an absolute approach (i.e.: one can calibrate the value by which the KPI falls for each assessment – e.g. if impact is large, this means that the KPI falls by 5%);

2. Or adopt a relative approach (i.e.: a very large impact means that the KPI will drop by 3 buckets).

He adds: “This means that each individual risk assessment now has a quantifiable impact on each objective’s KPI. Furthermore, these assessments come directly from the field and are not constrained by any theoretical strategic pre-assessment. Aggregation rules can stay simple (to encourage the risk management system to “signal” issues) or integrate correlation and secondary impact effect (to mirror a more plausible outcome).”

There can be more than one approach to consider too. He finds that hybrid approaches are plausible. However, he counsels that they “may threaten the coherence of the generated risk appetite profile.”

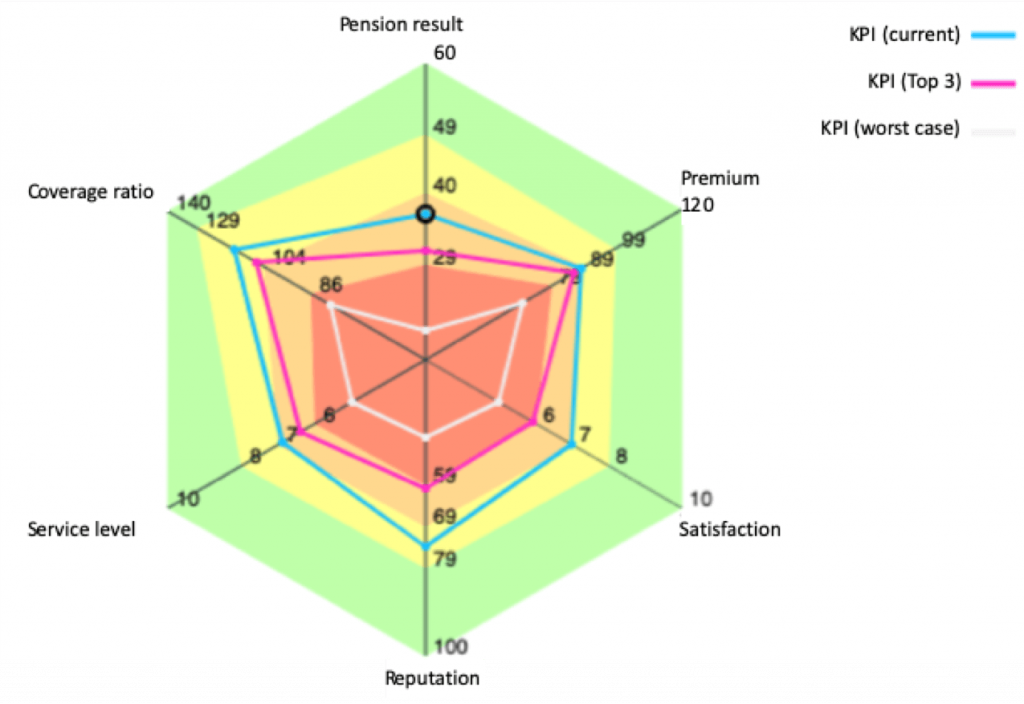

Proposing scenarios

He then explains the fifth step in the process: “As each of those individual risk assessments now embed a marginal impact on the retained KPI per objective, it makes it easy to propose to retain two main scenarios.” They are the following:

1. Worst case scenario: “What if the worst possible scenario materialises for each objective?”;

2. Top “X” scenario: “What is the impact of the top “X” risks for each objective?”.

At this stage, it’s possible to create ‘what if’ scenarios to permit the quick creation of alternative risk appetites, to compare the different outcomes with any current risk profile. Noblet says the key success factor is to accept that the “mechanics” behind this approach is not 100% mathematically correct:

“ngCompliance’s experience shows that an approach which is 100% correct but that no one understands triggers much fewer discussions and hence risk awareness at both Board level and field levels than a much more empirical, top-down or bottom-up connected approach.” He, therefore, concludes that only experiments can link theory and practice. To him, a scientific approach, based on empirical evidence, is ultimately the way fulfil an executable, realistic and sustainable risk appetite.

Special thanks to Thomas Wilson, Group CRO Allianz, Bas Hutink, Head of Control Pensioenfonds ING, Harald de Valck, Directeur Bestuursbureau SPW, and Louis Hakkenberg van Gaasbeek, Risk Manager Bestuursbureau SPW, for their incredibly valuable contributions, comments and knowledge.